History of the name Studer

The Surname Studer

-- Stude -- Staude -- Stutter -- Studr -- Studer --

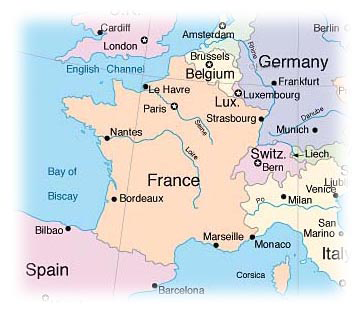

The name Studer is a very old and respected name. It is respected throughout Switzerland as well as the surrounding countries of France, Italy and Germany. The Studer name is mentioned in the records of the city of Zurich AS EARLY AS April 26, 1287. In the canton (state) of Luzern (Lucerne) it has been common since the beginning of the 15th century. There are a large number of people bearing the Studer name in the following Swiss cantons: Zurich, Bern, Luzern, Schwys, Zug, Fribourg, Basel, Solothurn, Aargau, Thurgau, St. Gallen and Wallis. In 1977 there were 475 Studers listed in the Zurich telephone directory. An even larger number were listed in the directory of the city of Bern. As of the late 1970's, "Studer" ranked as the third most popular surname in all of Switzerland, giving credence to the fertility and staying power of both the shrubs and the strong people who carry the name.

Studer, an old and revered name can be spelled and pronounced in several different ways. The pronunciation was often indicated by the path taken by the migrating family. Or perhaps the disposition and listening skills of the various clerics and clerks who recorded names. The standard spelling is S T U D E R, which is normally pronounced "stew derr" with the accent on the first syllable. In both France and Italy the name is most often spelled the same but pronounced as "stewed air" with an accent on the second syllable. In Germany the name is sometimes spelled S T U T T E R and pronounced "stewt terr" with only slightly more emphasis on the first syllable than on the second.

Studer, an old and revered name can be spelled and pronounced in several different ways. The pronunciation was often indicated by the path taken by the migrating family. Or perhaps the disposition and listening skills of the various clerics and clerks who recorded names. The standard spelling is S T U D E R, which is normally pronounced "stew derr" with the accent on the first syllable. In both France and Italy the name is most often spelled the same but pronounced as "stewed air" with an accent on the second syllable. In Germany the name is sometimes spelled S T U T T E R and pronounced "stewt terr" with only slightly more emphasis on the first syllable than on the second.

In the experience of this writer the most common mispronunciation of the name is "studd urr" with a soft vowel sound replacing the hard "U" as in "five card stud". There is no grammatical basis for this error, as a single consonant following a vowel almost always means that the vowel is to be pronounce with a hard or long sound. Perhaps the confusion can be traced to the legendary romantic reputation of Studer males, although this evidence is based primarily on hearsay and therefore should not be considered as scientifically accurate enough for inclusion in any publication.

The evolution of the name Studer is nicely illustrated by the following story. It involves the poor but proud peasant farmers of the beautiful little country of Switzerland. These poor peasants tilled the rather impoverished soil of the small valleys and hillsides of this often intimidating mountainous country. They eked out a meager living, surviving only through the protection and benevolence of their feudal lords. They fought the rocky soil on their miniscule plots of land, holding on as tenaciously as the many short, stubby, flowering bushes and shrubs which grew amongst the crags and the tors. In Schweisser-Deutsche or Swiss-German, the word for this type of low, ground hugging shrub is called "stude" or "staude". During the time period when everyone (including peasants) was taking a second family name, many of these Swiss farmers found that they could relate strongly to the persistent, stubborn little shrubbery of their homeland. These peasants took its name as their own, adding an "R" to the end of "Stude" personalized the noun and created the name Studer, which meant, quite literally "of the bush.

The history of naming

The development of family names in Europe can probably be traced to the expansion of the early Roman Empire. Previous to this time in history, a single name was normally sufficient to identify and differentiate individuals within a village, tribe, or clan. This was generally attributed to the small populations involved in these groups.

The early Romans (descendants of the first city building peoples the Etruscans), used single names. However, as their empire grew with more cities and tribes coming under one jurisdiction, accurate record keeping became more important. As a result of this growth and the efficient Roman bureaucracy, Roman citizens found themselves referring to their city name or clan name to separate themselves from other individuals with the same single name. For example, if a Centurion showed up at the door of young "Livinius" of the village of Rostus, demanding payment of past due taxes, Livinius might protest that surely the Centurion must be mistaken and perhaps is really looking for the know tax dodger Livinius of Prastis, a village some miles down the road. After much persuasion the Centurion would exit, leaving a visibly shaken Livinius who vows forevermore to be known as Livinius Rostus so as to avoid similar confusion, a possible long stretch in the local dungeon, or worse.

Many factors were used to determine additional names in these times. Such variables as tribal names, physical landmarks or regions; fathers name, mothers name and occupation were considered in establishing an identity in the community and empire as a whole. Some free thinking individuals even took on fourth, sometimes fifth names to commemorate some remarkable event or to call attention to a particularly unique ability or physical attribute. As the empire approached its latter days the litany of one man's name could and sometimes did become a ridiculous, long winded affair. If our friend Livinius Rostus had a father named Gregorius, who made swords for a living and walked with a noticeable limp, he could conceivably burden himself with the cumbersome name of: Livinius Rostus, son of Gregorius the lame, the creator of swords. Fortunately for us, the breakup of the Roman empire allowed people to slip back into their old habit of using one name. More than likely they were inclined to this so as to avoid wasting time on introductions.

During the remainder of the dark ages the use of a single name continued to be the custom among European people of all classes. This custom continued until about the late 900's AD.

Towards the close of this time period several noble families (from an area which is now considered to be Northern Italy) chose to revive the Roman custom of taking on a second name. Their motivation was simple- to separate and elevate themselves from the masses of common folk. A second name seemed to suit this purpose quite well and over the next several centuries the practice grew and was refined. As a result of this refinement, a belief developed that if a father was a powerful man, then he might seek some measure of immortality by passing on that power to his sons. The second name of this powerful man was a symbol of that power, and by passing it on to each succeeding generation the weight of this symbol lent a type of legitimacy to the dynastic designs of the parent. In this way a family could strive to maintain their status in the community over the course of many generations, often amassing great wealth and possessions not through competence or merit but simply because of their name.

By the 1200's AD these "family" names had become very common among the rich and were being taken on by more and more commoners who were seeking status for themselves and their progeny. This prevailed until virtually an entire population in some regions would have similar names. (Sigh, back to square one)

There seemed to be little hope of varied last names at this point in time. Enter one of the most significant events in European history to change the path of naming. The Crusades. A succession of wars waged by Holy Christian warriors against the "infidels" who occupied the holy land of Palestine, in particular the city of Jerusalem. As misguided, ill advised, racist and ultimately inconclusive as these ventures may have been, they did serve to open up the (mostly stagnant) sates of Europe to a world of new and exotic things. This in turn eventually lead to the blossoming of the Renaissance and the spread of European culture around the globe. As a result these noble, high minded yet misguided warriors brought with them an exposure to the practice of assuming family names. Soon nearly all Europeans had adapted the practice of using two names, one a given name and second a family name.

There were many methods available to the European patriarch of the middle ages to use in naming his family. Names sprung out of a family's environment, such as Brook, Stone, Forest, Lake etc., from one's occupation ie., Butcher, Taylor, Cooper, Baker, because of an identifying trait as in Barbarossa (red beard in Italian), Swift, Short, or Grosse (German for large) or simply from the father's given name, Johnson (John's son), or Pavlova (daughter of Pavel). Across modern America one can find an endless variety of surnames, arising from many different languages and cultures. Each has a unique and interesting story behind it.

The meaning of a word lies in the feeling of its creation and a family name can give us clues as to the origins of the family itself.